By Vijay Modi

In this article, project lead and professor Vijay Modi writes about the Columbia World Project Using Data to Catalyze Energy Investments. The project will be gathering data in Uganda to identify where small, rural businesses that could benefit from access to energy are located. Offering energy to these businesses could set off a chain reaction of positive economic growth. The approach ultimately aims to help move the world closer to the United Nations' goal of ensuring reliable access to energy for all by the year 2030

More than 800 million people around the world, many of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa, do not have access to electricity in their homes. As the United Nations and other major international organizations have recognized, achieving that access is critical for expanding economic opportunity, ensuring food security, and reaching other key measures of human development.

Providing household electricity access in places where it does not exist is challenging. Both public utility companies and private providers are finding the costs of bringing access to the home to be high, especially in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa. Evidence increasingly shows the advantages of providing energy to small businesses and farms (which is known in the energy field as providing energy for “productive use”). For energy providers to invest in supplying energy for productive use, they will need to work closely with governments, communities and experts in rural development, agriculture, and multilateral banks to identify areas where they can make successful targeted investments. And to do that, they will need data that shows where energy is – and could be – in demand.

To that end, Columbia University is initiating an effort – through a collaboration between Columbia World Projects and the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) – to gather data and create and deploy an open web platform that can track and project energy demand for productive use. In other words, the data will demonstrate where the small, rural businesses that could benefit most from access to energy are located. This is an effort we will pilot in Uganda, but we believe that the lessons we learn and the data-driven approach we develop will be replicable and will help move the world closer to the United Nations’ goal of ensuring reliable access to energy for all by the year 2030.

Recent efforts to expand electricity access to individual houses in rural areas has resulted in low usage. This is in large part because people in these areas have limited financial means to purchase electrical appliances and can’t afford a larger electricity bill. Providing energy access to agriculture and agro-related businesses could boost incomes to help close this gap. Agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa continues to be a source of livelihoods for the majority of the population. Increasingly, higher value crops, horticulture and floriculture are poised to provide farmers the next step up the income ladder, because they can bring in more profits per land area. These crops, however, are energy-intensive to produce, store and market, and benefit from the availability of electric power, both on the farms where they’re grown and at the markets where they’re sold. Offering energy to businesses in areas where this kind of productive agriculture is underway could set off a chain reaction of positive economic growth.

For energy providers to invest in building the infrastructure and the ecosystem to provide power to new areas, they will need to be able to identify geographic areas where demand is high enough, or likely to grow. Providing energy could set into motion a virtuous cycle of both energy and economic growth.

Our team of researchers is building the data systems that can offer current information on such viable areas. Several key elements will need to be in this place for our effort to be successful:

- We need to gather relevant field data at scale, using field visits combined with satellite imagery and machine learning.

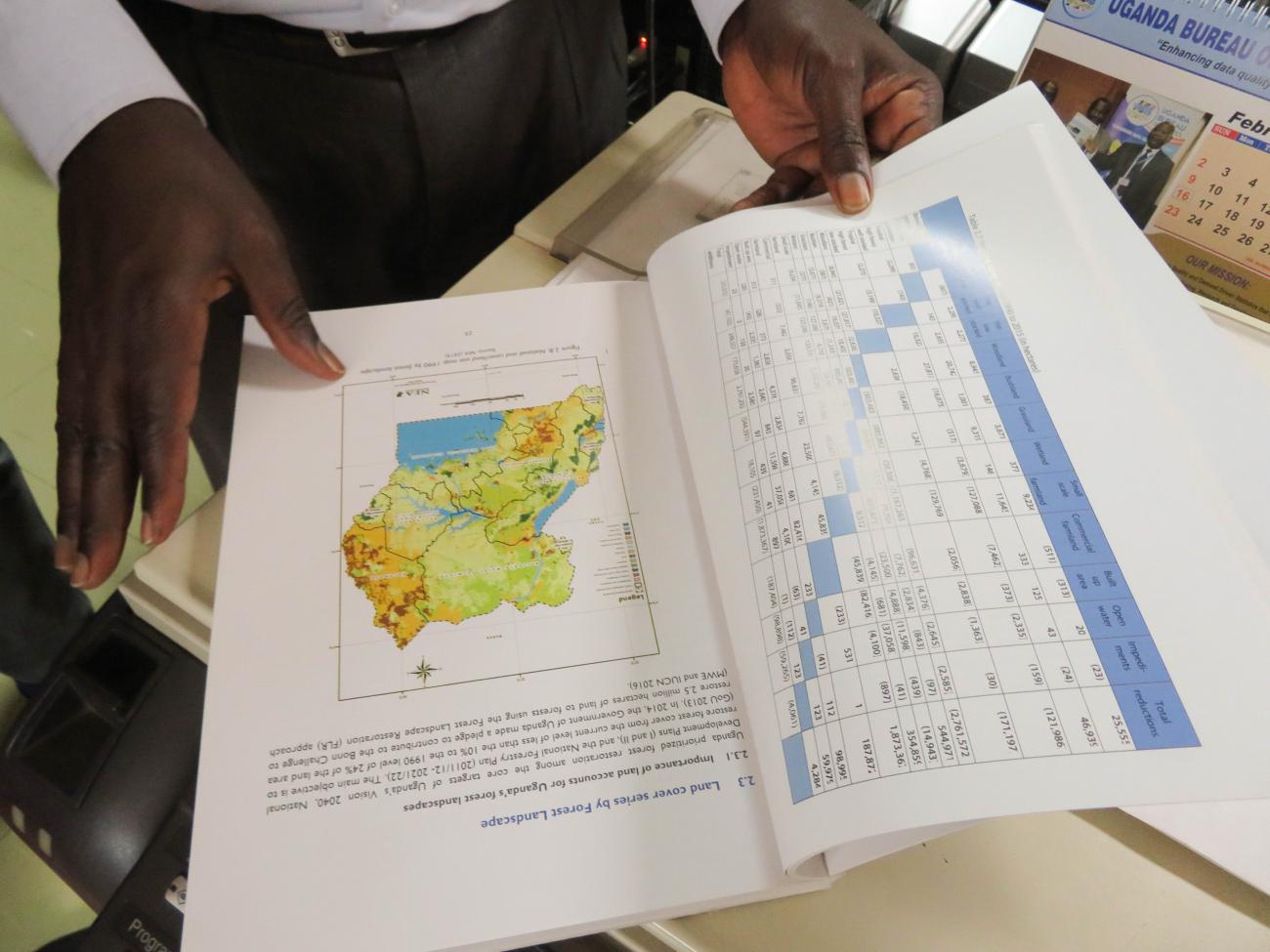

- The platform we build must be an open-source database that allows all levels and sectors of government to contribute and share the same information. A key part of that is embedding the platform within government agencies to ensure longevity and exploit economies of scale. This will eventually also allow governments to prioritize the equitable, efficient allocation of public resources, and will enable citizens and NGOs to oversee the data and report inaccuracies.

- The system should help break data silos. For example, providing energy to support agricultural businesses may require data on water, crops, soil, energy and markets that may otherwise reside in different domains of the government. Our project must bring this data together in one place.

- Our platform needs to be lean, replicable and easy to update.

- Our data needs to be comprehensible and accessible to all. In addition to governments, we want it to be accessible to owners of enterprises that serve farmers and providing them with irrigation, storage, processing, credit and agriculture inputs.

- We need to work with a range of local stakeholders and experts – from agriculture, to business owners to universities to federal statistics bureaus – who can help continue to shape the data platform, use the data we’ve gathered and progressively take over full ownership, hosting and updating of the platform and the analytical tools.

Our team at Columbia is well-situated to take on this challenge because of successes we have had already. A decade ago, a team that my laboratory led developed a system for tracking the infrastructure, staffing and services at every health, education and drinking water facility across Nigeria. This effort was carried out by government employees across Nigeria. They visited facilities armed with smartphones, collecting data and capturing photographs of the facilities and their GPS locations. We built a tool for this data collection called Formhub, derivatives of which are now widely used for surveys of this kind. The effort, called the Nigeria MDG Information System, was commissioned by the Nigerian government and subsequently transferred to their control.

The data has proven immensely valuable in responding to major floods in Nigeria and, more recently, in the country’s battle against the Coronavirus pandemic. The data platform creates a user-friendly way to identify each health clinic, make information accessible to health and energy providers, and makes it easy to visualize the geographic reach. Such information is essential for planning and logistics and to track supply chains of swabs, test-kits, personal protective equipment and medicines. Additionally, it could support efforts to ensure electricity at health clinics, an essential for vaccine storage. The development of the system was a truly Herculean effort, and the data it provides has allowed the country to identify gaps in health, education and water access, and to develop programs to close those gaps.

Our new energy data project is in many ways a leaner effort, thanks in large part to new developments in satellite imagery (also known as remote-sensing technology). For this new project, we are aided by satellite imagery to help prioritize and sample areas where demand for energy is likely to be high, such as areas where multiple crops are grown at once, is already being practiced. They may not have energy right now, but providing it could help quickly boost output, and lead to more income for the area, generating even more demand.

With years of experience and a clear plan of action in hand, the Columbia team is now piloting our project in Uganda. A coalition of institutions including the national government in Uganda, the World Bank, the African Development Bank, major foundations and leading organizations such as SEforAll will be crucial to take these efforts to scale. We are confident that once this method proves successful, we will be able to make a difference expand the reach much farther, to help countries realize their energy goals, and empower communities within those counties to improve their lives through development.